Coffea canephora: a little-known coffee species

Coffea canephora is becoming an increasingly important subject in the coffee industry. Although it has long been disavowed in favour of Arabica, the increasing difficulties and costs of Arabica production and recent research into improving the quality of canephora explain this renewed interest.

Canephora, robusta, arabica, what are the differences?

What are the differences between canephora and robusta?

It is essential to start by clarifying the terminology. The terms "robusta" and Coffea canephora are used interchangeably. This confusion illustrates the vagueness surrounding this species. Coffea canephora is a species of coffee plant, and robusta is a variety of Coffea canephora.

Taxonomy, i.e. the classification of living organisms, is constructed through an organisation that qualifies from the most global to the most precise. The coffee shrub is classified by its family, its genus, its species and then its variety.

More specifically, the coffee tree is a tropical plant in the Rubiaceae family, in the genus Coffea, which has a multitude of species. The best known is Coffea arabica, but there are also Coffea eugeniodes, Coffea liberica and Coffea canephora, as well as Coffea salvatrix, Coffea brevipes, Coffea racemosa and others.

So Coffea canephora is a species in its own right, different from Coffea arabica, and also has varieties, the best known being robusta, followed by conilon.

What are the differences between canephora and arabica?

The ideal growing conditions for Coffea arabica are at altitudes of 800 to over 2000 m, with a temperate equatorial climate (temperatures of 17°C to 27°C).

For Coffea canephora, the ideal conditions are between 100 and 1500 m altitude, with an equatorial climate (temperatures between 24°C and 30°C).

The entire Coffea genus has 22 chromosomes, with the exception of Arabica. While Arabica is autogamous (it reproduces by self-fertilisation), Canephora is allogamous (it reproduces by cross-fertilisation). This cross-fertilisation leads to greater genetic diversity within Coffea canephora plantations, making it more difficult to identify varieties and terroirs.

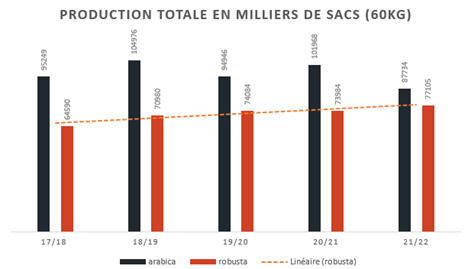

Arabica and Canephora production (in thousands of bags), Foreign Agricultural Service/USDA December 2021

As it spread across the continents, new botanical varieties were developed. The best known is robusta. We can also mention the kouillou (fruits and beans smaller than robusta). Conilon is a variety native to Brazil. Its name is thought to be a mistranslation of kouillou (the "u" has become an "n"). Other varieties include gimé and niaoulé from West Africa. Coffea canephora is easy to identify visually. The bean is smaller than Coffea Arabica and more spherical in shape.

Visual comparison Coffea canephora (left) and Coffea arabica (right). Photos by Jérémy Limousin, Belco Quality Laboratory

Discovering Coffea Canephora

Canephora was discovered late in the 19ᵉ century on the banks of the Lomami River in the Democratic Republic of Congo (Herrera and Lambot, 2017). At that time, the country was a Belgian colony.

At the beginning of the 20th century, via the Belgian botanical nursery, the country began moving the first robusta varieties to the island of Java. This was followed by planting in India, Uganda and Côte d'Ivoire.

In 1912, the first varieties from the Coffea canephora species reached the American continent, with the first crops being grown in Brazil.

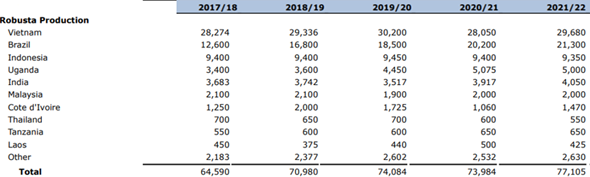

Coffea canephora production worldwide, Foreign Agricultural Service/USDA, December 2021

Today, Coffea canephora is grown in the following countries, led by Vietnam, Brazil and Indonesia. Production in Brazil has risen sharply over the last 5 years. The Espirito Santo region accounts for between 70 and 80% of national conilon production.

Focus on conilon production in the Espirito Santo region

Over the last fifty years or so, conilon plants have gradually replaced arabica plants. Rafael Marques, Belco & FAF Coffees partner and founder of the 'Lado a Lado' project, points out that despite the presence of conilon for more than a century, research dedicated to improving its aromatic complexity, productivity and disease resistance has developed in less than 30 years.

200 clones have been tested. New, higher-quality varieties have been developed, such as diamante, jequitiba, centenario and vitoria, which are produced in the Espirito Santo terroir at high altitudes for canephora.

Rafael told us that demand for quality conilon was growing, and that it could even be used as a pure origin coffee like certain Arabicas. The first batch of Espirito Santo conilon will arrive in Belco warehouses in December 2022.

The chemical composition of Coffea Canephora compared to Coffea Arabica

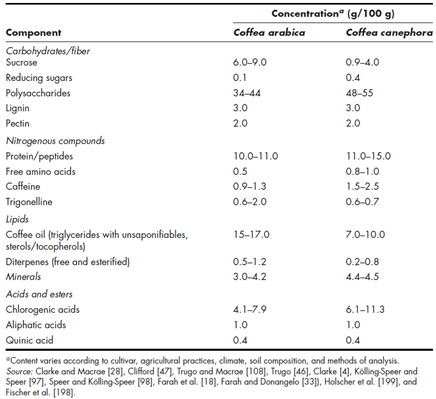

To understand the specific aromatic profile of canephora, it is interesting to look at its chemical composition and compare it with arabica. Lindsay et al (2012) present a table comparing the two species.

Composition chimique du café vert Coffea arabica et Coffea Coffea canephora - Source : Coffee : Emerging Health Effects and Disease Prevention, Chapitre 2, 2012

The quantities of sucrose, caffeine, trigonelline and chlorogenic acids mark the major differences between these two species.

High concentrations of chlorogenic acids and caffeine have a negative impact on the quality of the cup, while low levels of sucrose and trigonelline are responsible for its low complexity. During roasting, chlorogenic acids break down into lactone and quinic acid, which have a bitter flavour.

As caffeine does not break down during roasting, its high level will also add bitterness. Sucrose is an essential element in the Maillard reaction, breaking down into glucose and fructose during roasting. Trigonelline will also break down into volatile components. In small quantities, these two chemical compounds will result in low aromatic complexity.

Poisson et al (2012) add that the large quantity of free amino acids in canephora will have a negative impact in the cup with the presence of earthy or even animal notes.

This species has a higher quantity of polysaccharides, the main components of cellulose. These polysaccharides protect the beans from external contamination and deterioration, giving Coffea canephora better ageing than Arabica. They are also responsible for the thicker body of the beverage.

Lingle and Menon (2017) point out that the Specialty Coffee Association of America (SCAA) created the Specialty Coffee Institute (SCI) in 1995 to develop a scientific approach to evaluating specialty coffee. In 1998, when coffee prices plummeted and fell below production costs, SCI became CQI (Coffee Quality Institute).

The Institute's remit shifted towards the continuous improvement of coffee quality and producers' living conditions. It was at this point that a method was formalised through the SCAA tasting protocol. It was 15 years later, in 2010, that the CQI created the tasting protocol for canephora.

The canephora has mainly been cultivated for its resistant and productive properties. In recent years, the scientific community has been working on varieties with complex aromatic profiles. Some growers are investing as much attention in cultivating this species as they do in Arabica. The late appearance of associations and groups working for the quality of Coffea canephora, as opposed to those for Arabica, highlights a quality potential that needs to be exploited.

What are the vectors for improving the quality of the species?

With a view to improving quality and ensuring the long-term future of the sector, it is important to study the various factors affecting the production and flavour profile of Coffea canephora (Linge and Menon, 2017).

Like Arabica, altitude will have a positive impact on cup quality. Above 1000m, the slower maturation of the bean and its higher density ensure a more complex profile. Shade will also improve the aromatic quality (according to studies carried out in India, a country heavily involved in canephora research).

Historically, canephora has been processed using the dry or 'natural' method. The 'washed' or wet process is much more complex than for Arabica. Coffea canephora's mucilage is thicker and stickier, making it more difficult to wash, with the risk of damaging the bean during the process and causing the "cut" defect (official SCA defect, physical embrittlement of the bean). Fermentation can also be a problematic stage due to the canephora anatomy (thick mucilage) and the higher temperatures at these altitudes. Fermentation can take more than 72 hours, compared with 24-48 hours for Arabica. Extreme care and precision are needed to avoid the "sour" defect (official SCA defect, yellowish grain with a vinegary odour).

In the interests of canephora production, growers have tended not to explore this type of process. It has been shown that the wet process, with rigorous, selective picking, controlled fermentation and thorough drying, improves cup quality, with brighter acidity, lower bitterness and better overall clarity in the cup. Honey" or "Pulped natural" processes are also a new way of improving quality.

The key to improving quality lies in massive investment in awareness-raising programmes and support for producers. It is important to structure tasting and to calibrate professional tasters to the standard profiles as well as to the new aromatic profiles of Coffea canephora.

How to enjoy Coffea canephora?

The official tasting sheet

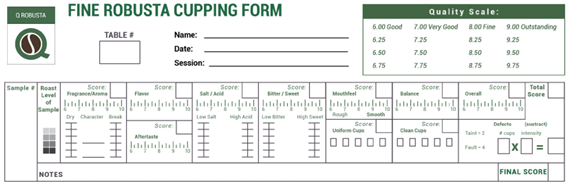

In 2010, the Q Robusta or R-Grader programme was created through collaboration between the Coffee Quality Institute (CQI) and the Uganda Coffee Development Authority (UCDA).

The aim is to formalise a common language of Coffea canephora quality through a specific tasting grid. The R-Grader taster will focus on 10 categories to assess each coffee. Some categories are common to the Arabica tasting grid: 'Fragrance/Aroma', 'Flavour', 'Aftertaste', 'Balance', 'Uniform cups', 'Clean cups' and 'Overall'. Others are specific to Coffea canephora, such as 'Bitter/sweet aspect ratio', 'Mouthfeel' and 'salt/acid aspect ratio'.

The score obtained from this rating is used to classify into three categories: 'Standard' (<76), 'Premium' (76-80) and 'Fine Robusta' (>80).

The "Bitter/sweet aspect ratio" is used to assess the perception of bitterness compared to the perception of sweetness. Fine Robusta" will have a greater perception of sweetness than conventional robustas.

"Mouthfeel" characterises the body and tactile sensations. A silky texture will be perceived as qualitative. Weight can also be taken into account in the final score.

Finally, the "Salt/acid aspect ratio" category analyses the balance between the perception of salty and acidic flavours. Canephora may contain a high level of potassium (salty taste) and low concentrations of citric acidity. Fine Robusta' will have a lower perception of salinity (less potassium).

Official CQI tasting sheet for Fine Robusta

Coffea canephora tasting at Belco

In July 2022, we tasted 35 coffees from 9 different origins (Brazil, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, India, Indonesia, Uganda, Rwanda and Vietnam). This tasting was carried out by 12 people from the Belco teams. The selection of canephoras was made up of offers from new partners and coffees already present at Belco.

A comparison was made in order to situate these new coffees and our existing range in the current market and to explore new options for Belco. With climate change, increased freight and potential unexplored qualities, we aim to deepen our knowledge of Coffea canephora and Fine Robusta.

For the tasting we used the CQI ranges: Standard <76, Prémium 76-80 and Fine Robusta 80+. To facilitate the simultaneous tasting of all 35 coffees, the exercise was based on a simplified allocation of each coffee to one of these three categories, awarding 1 point for the 'Standard' range, 3 for the 'Premium' range and 5 for the 'Fine' range. The average of the scores forms the overall score.

Following these results, we introduced the use of CQI categories internally at Belco, imported new canephoras and introduced a new range with coffees rated 83+. These coffees are now tasted separately from Arabica to avoid comparison.

In conclusion

Still associated with the image of an inferior product, Coffea canephora is undergoing a positive evolution in terms of production and quality within the industry. Climate change and rising production costs are accelerating this change. Considering the ecological impact of production, it is important to highlight the adaptability of canephora to high temperatures. This adaptability means that the species can be grown without the need for many chemical inputs.

The quality dimension of the canephora sector is also evolving. We are now seeing new cup profiles, work on fermentation and yeasts, and even participation in international barista championships.

For a long time, canephora suffered from the comparison with arabica. We need to gradually move away from this comparison, which is being made out of ignorance. Let's stop demonising Coffea canephora and "robustas", which are only at the beginning of their development! We should also point out that they are genetically part of the resistant "arabica" varieties (Hybride du Timor, Catimor, Castillo, Ruiru 11, Marsellesa), which are widely grown today.

Canephora has an important role to play in the future of the coffee industry, with an increase in its cultivable area, its quality, a reduction in its overall ecological impact and its distinct contribution to our espressos.

Bibliography

- Herrera J.C. and Lambot C. (2017), "The Coffee Tree - Genetic Diversity and Origin" in The Craft and Science of Coffee, Chapter 1

- Lindsay J., Carmichael P-H., Kröger E. and Laurin D. (2012) "Coffee: Emerging Health Effects and Disease Prevention", Chapter 2

- Linge T.R and Menon S.N (2017), 'Cupping and Grading - Discovering Character and Quality' in The Craft and Science of Coffee, Chapter 8

- Poisson L., Blank I., Dunkel A., and Hofmann T. (2012), "The Chemistry of Roasting-Decoding Flavour Formation" in The Craft and Science of Coffee, Chapter 12

Jean Etchats, Quality Director, and Denis Mialocq, Training Manager

Did you like this article? Share it with your community: